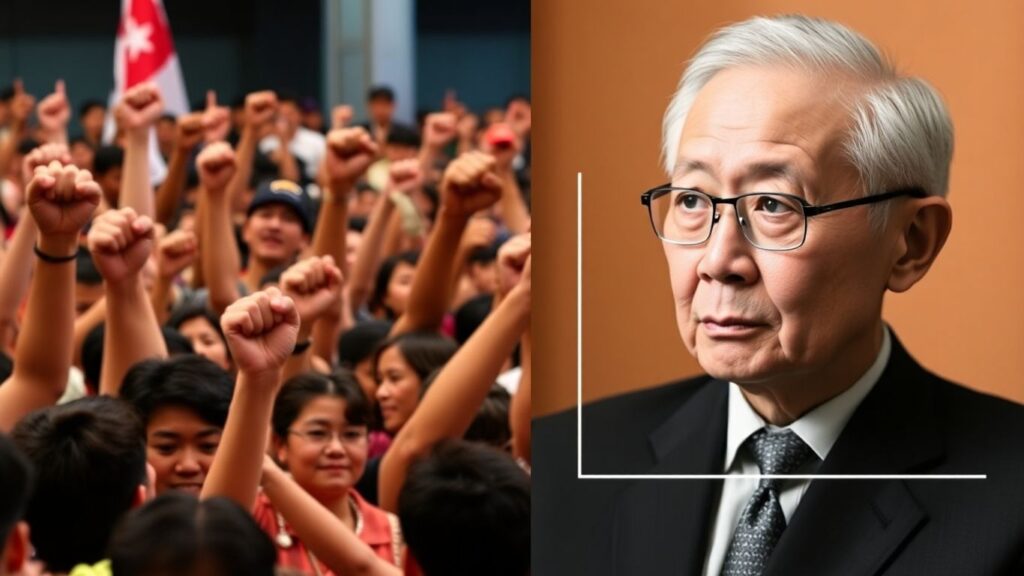

Why Are Anti-Immigration Protests EVERYWHERE? Lee Kuan Yew on Multiculturalism & Low Birth Rates

Across the globe, from the UK to Australia, Japan to the Netherlands, and even with new visa fee changes in the US, anti-immigration sentiments seem to be on the rise. It’s a complex issue, and Lee Kuan Yew’s thoughts on immigration and multiculturalism, especially when facing falling birth rates, feel more relevant than ever.

Key Takeaways

- Falling birth rates in developed nations are a major challenge, making immigration necessary for economic stability.

- Deep-seated biases are natural, and managing multicultural societies requires acknowledging these human instincts.

- While monocultures have advantages, they also face disadvantages, as seen in China and Japan.

- Multicultural societies, like America, can be dynamic but require careful management to avoid social friction.

- Singapore’s approach involves fostering a national identity while respecting diverse cultures, but relies on immigrants’ children becoming citizens.

- Openness to immigration can lead to economic resilience, as demonstrated by Singapore compared to Japan.

The Challenge of Falling Birth Rates

It’s a trend happening everywhere: birth rates are dropping in developed countries. As women get more education and join the workforce, having children becomes more expensive. The cost of raising a child can mean a significant loss of income, especially if one parent stays home. This is a big problem for countries like Singapore, which are increasingly counting on immigrants to keep their economies from collapsing. Without them, by 2050, you could have a situation where only one and a half working people are supporting two retirees. That kind of burden could even cause the brightest young people to leave.

The Human Side of Multiculturalism

Countries like America, Australia, and Singapore are often seen as successful examples of immigrant societies. But even Lee Kuan Yew recognized that managing a multicultural society isn’t easy. He believed that our natural, deep-seated biases – our tendency to stick with people who look and act like us – are a real challenge to social harmony. These racial preferences aren’t going away, and pretending they don’t exist won’t help.

He saw this play out not just in Singapore’s own history with racial tensions, but also globally. Minorities have often faced tough times and even violence in different societies. Europe’s struggles with integrating immigrants and America’s own experiences as a multicultural nation show that it’s a difficult balancing act.

Monocultures vs. Multiculturalism

When you have a society that’s mostly one culture and one language, like in China, there’s a certain cohesiveness. People share the same language, culture, and often race. This can create a strong sense of unity, where people are willing to sacrifice for the good of the community. China has shown it can rebuild itself even after invasions because of this deep-rooted connection.

However, monocultures have their downsides. Japan, for example, has a very low birth rate and is resistant to immigration. This means they’re facing a shrinking workforce where fewer people will be supporting more retirees. While they might have a strong internal identity, their closed-off approach could lead to economic stagnation.

Multicultural societies, on the other hand, can be incredibly dynamic. America’s success, particularly in places like Silicon Valley, is a testament to its ability to attract talent from all over the world. This mix of ideas and perspectives fuels innovation. But it’s not without its challenges. Different languages and cultures can bring their own baggage, leading to divisions and feuds, as seen with immigrant groups maintaining old rivalries in new countries.

Singapore’s Balancing Act

Singapore aims to create a distinct national identity without forcing everyone to become the same. The idea is to keep individual cultures while embracing a shared sense of being Singaporean. But this relies on immigrants’ children becoming Singaporeans themselves. If the native population isn’t reproducing enough, the country becomes more dependent on migrants to maintain its population and economy. This raises questions about whether the national identity being built could be diluted.

Lee Kuan Yew believed that a nation needs more than just a few decades to build a deep sense of identity and cohesiveness. He pointed to Sweden, where a high-trust society built on shared culture and social benefits is being tested by a large influx of refugees. If the wealthy lose faith, they might leave, potentially unraveling the social fabric.

The Necessity of Immigrants

Despite the difficulties, Lee saw clear advantages in embracing immigrants. He argued that Singapore’s openness makes it more economically resilient than countries like Japan. Singapore can make up for its small population by attracting bright individuals from around the world. This influx of talent is seen as necessary for growth and progress in a competitive global landscape.

Ultimately, managing immigration and multiculturalism is a constant balancing act. It’s about finding unity while respecting deep-seated biases and meeting economic needs. Lee Kuan Yew believed that multicultural nations, by accepting differences and encouraging compromise, can not only survive these challenges but thrive, fostering a spirit of coexistence that has been key to Singapore’s success.

Responses