Russia’s Pivot East: From Greater Europe to Greater Eurasia

For centuries, the world has largely revolved around a Western-centric view, shaped by maritime powers and their control over global trade routes. However, a significant shift is underway, with Eurasian powers like Russia and China forging new connections and challenging the established order. This transformation marks a move away from a Western-dominated globe towards a more multipolar Eurasia.

Key Takeaways

- The historical dominance of maritime powers is being challenged by the rise of land-based Eurasian connections.

- Russia’s strategic pivot away from Europe towards Asia signifies a major geopolitical realignment.

- China’s Belt and Road Initiative and other Eurasian integration projects are reshaping global trade and infrastructure.

- The West’s attempts to maintain hegemony are inadvertently strengthening Eurasian cooperation.

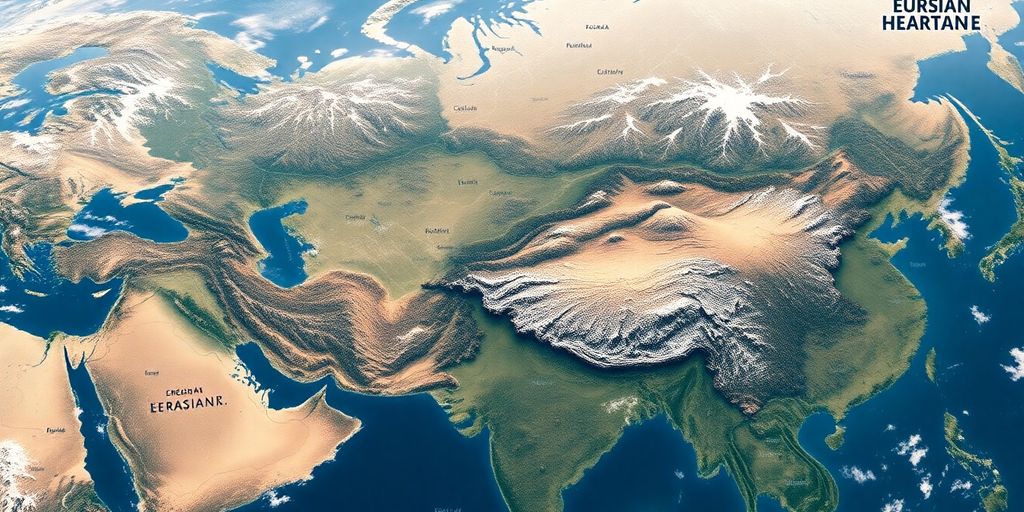

- Geography continues to play a critical role in shaping global power dynamics.

The Age of Maritime Dominance

For about 500 years, European maritime powers have connected the world, starting in the early 16th century. Before that, the ancient Silk Road connected Eurasia through land and sea routes, facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and technology. This ancient network was decentralized, often managed by nomadic groups. The Mongol Empire was the last major force to maintain these routes before their decline in the 14th century.

The rise of explorers like Columbus and Magellan ushered in a new era. European maritime powers centralized control over key ports and shipping lanes, creating a system where controlling choke points was more important than conquering territory. This led to a more exploitative relationship with other parts of the world, as noted by Adam Smith, who hoped for a future with less power inequality.

This maritime dominance eventually led to the Pax Britannica in the 19th century, where Britain controlled the seas and thus global trade. This hegemony later passed to the United States, which continued to control these vital sea lanes. Britain also gained a significant advantage through the Industrial Revolution and its financial power, further solidifying its global position.

The Great Game and the Heartland Theory

By the 19th century, a new geopolitical reality emerged. Russia’s attempt to reach British India through Central Asia during the Napoleonic Wars showed that land powers could also pose a significant threat to maritime dominance. This sparked the "Great Game," a prolonged rivalry between Britain and Russia for control over Central Eurasia.

The Crimean War (1853-1856) highlighted Russia’s industrial and infrastructural weaknesses, leading to major reforms and rapid industrialization, including the construction of railroads across Central Asia. These railroads often followed the paths of the ancient Silk Road, extending Russian influence.

Meanwhile, in Britain, the "Heartland Theory" was developed by Halford Mackinder. He argued that controlling Eastern Europe was key to dominating the "world island" of Eurasia, and thus, the world. Mackinder warned that the development of transcontinental railways could shift power away from maritime nations towards land-based powers, a significant threat to British hegemony.

This theory heavily influenced British and later American geopolitical strategy. The US adopted a policy of "Eurasian containment," aiming to prevent any single power from dominating the Eurasian landmass. This involved maintaining military presence on Eurasia’s periphery, both in Europe and the Pacific.

Russia’s Western-Centric Path and the US Response

Following the Bolshevik Revolution and the establishment of the Soviet Union, Russian émigrés like Petr Savitsky developed "Eurasianism." They argued that a Russo-German alliance would be ideal to counter maritime powers and that Russia should embrace its Eurasian identity rather than trying to be a Western European maritime power. They believed maritime powers relied on "divide and rule" strategies to maintain control, and Eurasian powers should seek cooperation.

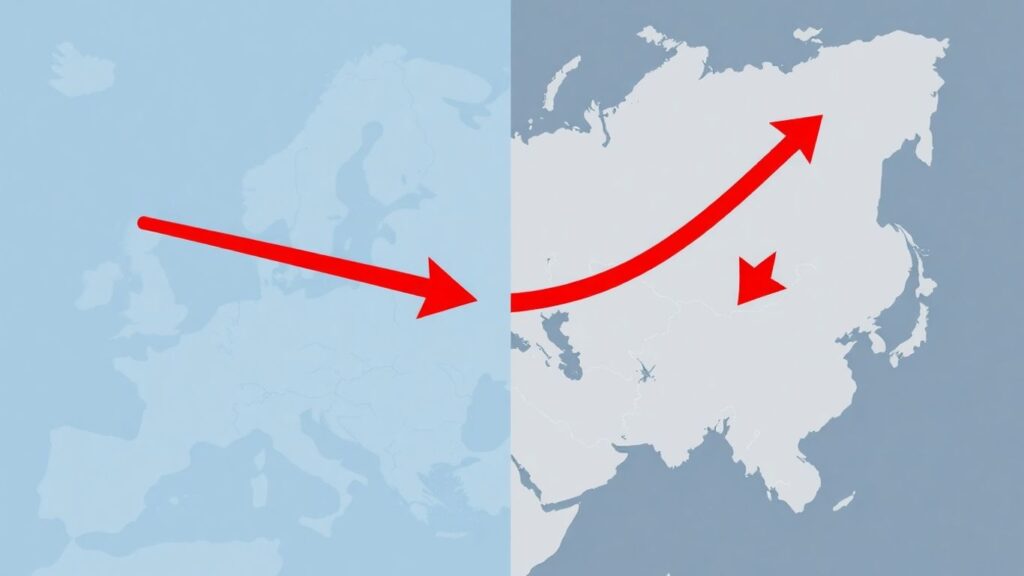

For centuries, Russia had attempted to modernize by looking west, a strategy that often led to its access to maritime routes being restricted. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia continued this Western-centric approach, pursuing a "Greater Europe" project. However, this weakened Russia and presented an opportunity for the US to solidify its hegemonic position.

The US "Wolfowitz Doctrine" (1992) aimed to prevent any potential rival from emerging in Eurasia. This strategy involved maintaining security dependence on the US and preventing integration between major Eurasian powers like Germany and Russia. Zbigniew Brzezinski, a key strategist, emphasized the need to keep Eurasian powers divided and maintain US security dependence, viewing Russia as a "geostrategic black hole" that could be exploited.

US-led initiatives, like pipeline projects, were designed to sever Central Asia from Russia and China, reinforcing a hegemonic vision of Eurasia.

The Pivot to Greater Eurasia

Around 2014, two major events signaled a shift in the global order. The NATO-backed coup in Ukraine ended Russia’s hopes for integration into a "Greater Europe," positioning Ukraine as a frontline against Russia. Simultaneously, China, having gained significant economic power, began challenging the US-led international system.

China launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, aiming to revive the Silk Road through extensive infrastructure development. Ambitious industrial policies like "Made in China 2025" and the establishment of new financial institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) further signaled China’s growing influence.

With both Russia and China losing faith in the US-led system, a new "Greater Eurasia" concept began to emerge. Russia abandoned its Western-centric policies and embraced cooperation with China. This pivot, driven by Western efforts to isolate Russia, pushed it further East, creating a powerful Eurasian bloc that Mackinder had warned about.

The BRI connects Eurasia through railways, highways, and seaports, fostering trade, industrial cooperation, and the use of national currencies. This multipolar approach offers an alternative to a single center of power. Russia is also developing its own projects, like the East-West corridor along the Trans-Siberian Railway and the Northern Sea Route along the Arctic, offering faster and cheaper transportation outside US Navy control.

Harmonizing Interests in a Multipolar World

Russia and China, along with other Eurasian nations like Iran and India, are pursuing various integration initiatives. While these projects differ, they share a common goal: improving relations and finding political solutions to connect the continent. No single power can impose its will; instead, interests must be harmonized.

Western assumptions that Russia and China would clash over Central Asia have not materialized. Instead, they are working towards a multipolar system, harmonizing their efforts within organizations like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and BRICS. These initiatives now encompass not just physical infrastructure but also digital and energy corridors, technological partnerships, and the use of national currencies for trade.

The alternative to this Eurasian multipolar system is what could be described as an "empire of chaos," reliant on alliance systems and perpetual conflict, designed to keep Eurasian powers divided.

The Decline of Hegemony and the Rise of Eurasia

US global primacy, while still significant, is not sustainable and is in decline. A weakening hegemon often becomes more aggressive, resorting to economic and proxy wars, as seen in the US tech war against China and the conflict in Ukraine. The West’s attempts to seize Russian sovereign funds, while intended to prevent rivals, are instead incentivizing other nations to seek economic partnerships within the Eurasian framework.

The West’s resistance to Eurasian cooperation stems from a desire to preserve maritime power dominance, failing to recognize that the geopolitical landscape has changed. Russia no longer has the capacity or intention to dominate Eurasia; the threat is now a multipolar system. The US’s insistence on a hegemonic model, rather than a balance of power, leads to strategic missteps.

Actions like seizing Russian central bank funds and attacking Chinese tech companies are making the world wary of the Western financial system and supply chains, pushing nations towards alternatives. This tribal mindset in the West, where dissent is seen as siding with adversaries, leads to narratives detached from reality.

Europe has much to gain by embracing multipolar realities and adjusting to the new international distribution of power. However, there’s a reluctance to accept these changes. As Machiavelli noted, people often see things not as they are, but as they wish them to be, leading to ruin.

In Russia, sentiments are shifting, echoing Dostoevsky’s observation that Russians are both Asiatic and European. The mistake of the past two centuries, he suggested, was trying to be "true Europeans" and earning only hatred. The future, it seems, lies in Asia. Geography, as always, matters, and a new Eurasian world order is taking shape, with efforts to prevent it only accelerating its development.

Responses