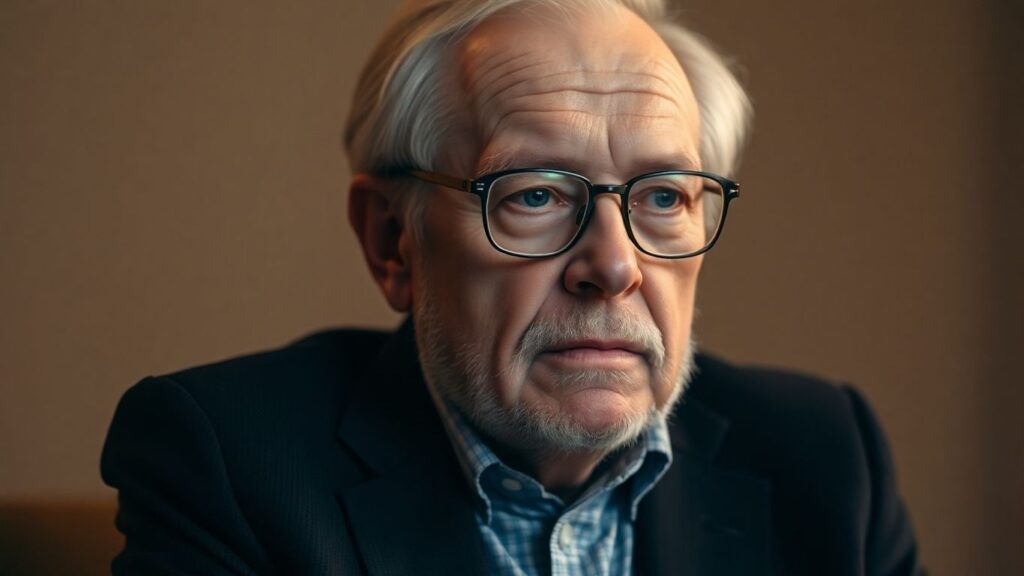

Charlie Munger on Common Sense, Investing, and Avoiding Folly

In 2008, Charlie Munger, the legendary investor and partner of Warren Buffett, sat down at Caltech for the DuBridge Distinguished Lecture. Instead of a typical lecture, it was a conversation, a format that honored the spirit of Lee DuBridge, a former president of Caltech who believed in bringing diverse minds together to discuss science and technology.

Key Takeaways

- Common Sense is Uncommon: What people call common sense is often just uncommon sense – the ability to operate across various situations without making major mistakes.

- Inversion is Powerful: Tackling problems by looking at them backward or from a different angle can lead to surprisingly simple solutions.

- Avoid Folly: A key strategy for success is identifying and actively avoiding the mistakes and foolishness of others.

- Multidisciplinary Thinking: Don’t be confined by academic boundaries; grab big ideas from anywhere and use them to solve problems.

- Know Your Limits: Understanding the edge of your own competency is crucial to avoid disaster.

- Simplicity is Key: Aim for simple explanations, but not oversimplified ones. Look for multiple causes in complex social science issues.

- Integrate Knowledge: Connect ideas across different disciplines; this is a less crowded mental road with fewer competitors.

The Value of Uncommon Sense

Munger kicked off the discussion by talking about "common sense," which he argued is really "uncommon sense." It’s not about being good at one narrow thing, but about being able to navigate a wide range of human activities without making big blunders. He shared how he learned this early on by observing others who were better than him in various fields. Instead of trying to be the best at everything, he focused on avoiding the mistakes others made. This strategy, he found, worked remarkably well.

He also highlighted the power of inversion, a technique where you twist a problem around backward to find the solution. He gave an example of a riddle he posed to his children: naming an activity where the national champion won on two separate occasions, 65 years apart. While many struggled, his physicist son quickly solved it by realizing the activity couldn’t be athletic (due to age deterioration) or chess (too difficult to master late in life), leading him to checkers. This simple inversion cracked the problem.

Collecting Inanities and Avoiding Folly

Munger described himself as a "collector of inanities" – cataloging foolishness in his head. He finds this a wonderful and amusing activity, unlike collecting stamps or other material things where you might hit financial limits. There’s always an endless supply of foolishness to collect, and it provides a constant source of learning. By identifying folly, he aims to gain an advantage without necessarily needing to be exceptionally skilled in any one area.

He stressed the importance of avoiding folly and shared how he actively tries to identify and steer clear of it. This approach, combined with grabbing big ideas from various disciplines and using them to solve problems, has been a lifelong strategy. He doesn’t pay attention to the territorial boundaries of academic subjects, instead, he collects powerful ideas wherever he finds them.

The Power of Multidisciplinary Thinking

One of Munger’s key strategies is integrating knowledge across disciplines. He noted that there’s little reward for connecting ideas from different fields, especially if they aren’t your own. This makes it a less crowded mental path, where one can operate with less competition. When ideas from different disciplines conflict, he looks for synthesis. If he can’t find a clear answer, he tries to figure it out and uses his best approximation until it improves.

He also touched upon Occam’s Razor and a corollary attributed to Einstein: "Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no more simple." Munger added his own supplement for messy social sciences: when observing a "lollapalooza" (a big, extreme) result, look for a confluence of multiple causes. He illustrated this with the example of how the Moonies converted people, which involved stress and psychological techniques, a complex interplay of factors rather than a single cause.

Critiquing Social Sciences and Finance

Munger expressed frustration with how social sciences are often taught, suggesting they are poorly executed and lead to incompetent practitioners. He believes a lack of multidisciplinary competence is a major issue. He used the example of economics, where many struggle to understand situations where raising prices can increase sales (like luxury goods), or even more basic concepts like bribing purchasing agents. He argued that a lack of integrated thinking leads to missed opportunities and poor decision-making, both in academia and in business.

He extended this critique to Wall Street, drawing parallels between the complex financial instruments being created and the "common mode failures" he experienced with hurricane insurance. He criticized the creation of overly complicated securities like collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), which were rated AAA but carried hidden risks. He also condemned the accounting practices that blessed these complex instruments, leading to a "diseased outcome" and a failure of professionals and regulators.

Education and the Future

Discussing education, Munger praised Caltech as a remarkable institution that produces high-quality graduates. He contrasted this with the failures in urban education systems, attributing some of the problems to the flight of competent people to the suburbs. He also touched upon the rise of China, acknowledging it as a significant competitive force but emphasizing the need to get along with them, especially given their nuclear power status.

When asked about future issues, Munger was less concerned about environmental collapse, believing human ingenuity would find solutions, particularly in energy. However, he expressed greater concern about more existential threats like nuclear war or the successful mass use of pathogens. He also reflected on the nature of competition, noting that while specialization is important, developing a broad, common sense competency is also vital for navigating life and avoiding the pitfalls of narrow thinking. He concluded by emphasizing that while specialization is necessary, it shouldn’t preclude the development of a generalized competency and the ability to learn from others’ mistakes.

Responses